This article was first published in "

Frequency Magazine"

– June 2008.

Canvasses and canvas boards available in art shops are generally primed with a white primer. However, it is not pleasing to the eye to have white spots showing through the paint in a finished work. One obvious answer to this common problem is to tone your canvas. You will find other benefits to toning canvasses.

- Toned canvasses make it easier to establish correct tones for your painting. The background colour on the canvas will act as your mid-tone and it becomes easier to establish the lighter lights and darker darks and key the painting. If you start from a white canvas, your dark tones will appear darker than they are and you will struggle to establish your light areas as you can’t get lighter than the white of the canvas.

- Toning the canvas allows you to choose to start from a warm or a cool background and set the general tone of your painting.

I am now going to describe two different methods to create a toned canvas.

1. Toning the canvas by applying another layer of gesso

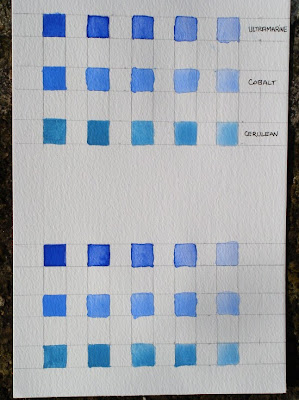

One of the methods I use consists in mixing some acrylic gesso (you can buy jars of acrylic gesso primer in any art shop) in an old ice-cream tub with a small amount of acrylic colours in order to tint it. I then apply the tinted gesso onto the canvasses or boards I have purchased with a large brush. By using yellow ochre, vermillion red and ultramarine blue in various combinations and proportions, you can obtain a good range of shades from cool grey to warm pink.

2. Toning the canvas at the last minute

2. Toning the canvas at the last minute

If you don’t have the time to apply a layer of tinted gesso, you can tone your canvas at the last minute with washes of colours. Earth colours work well to establish tones. Yellow ochre is a semi transparent colour, dries fairly quickly and can be used to establish the mid-tone areas. For darker areas, use a wash of Raw Umber (semi-transparent) or Burnt Umber (dark and transparent). These colours should be used diluted with plenty of thinner. It does not matter if the paint runs down the canvas, you are only laying the underpainting.

Once you have put your mid-tone and dark tone areas in place, wrap a rag around your index finger and remove the paint where you want to place light areas. This will leave a pale film of the original colour and will create smooth transitions between light and dark areas. Because the whole canvas is covered with washes, these areas will appear light, even if not totally white. If you need to create hard edges, for instance for the light side of a building, dip a flat hog brush in your thinner and remove the paint with the tip of the brush. Wash the brush on a rag and start the process again until you have cleared all light areas.

Old masters were using earth colours for their underpainting because these colours were cheap and had good siccative power. The other advantage of earth colours is that they won’t muddy your colours when you apply subsequent layers. They are versatile and will go well with cool blues or warm colours.

Instead of using eath colours to tone your canvas, another method I like, is to use complimentary or contrasting colours for your first wash. For instance, you would apply a wash of red paint to cover an area where you plan to paint some grass. This way of doing it present at least two advantages:

- Some of the underpainting will show through you subsequent layers and will “make the colour sing”.

- If the subsequent complimentary colour is applied “in the fresh”, a certain amount of blending with occur and create neutral tones.

Your first stage of the painting will present a wild colourful aspect which is very uplifting and will give you a sense of freedom.

I recommend that you experiment with toned canvasses and see if they fit your style and technique.

Related articles

by Ambroise Vollard (English translation)